Berklee today is the official alumni publication of Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. It is a forum for contemporary music and musicians.

Issue link: http://berkleetoday.epubxp.com/i/106074

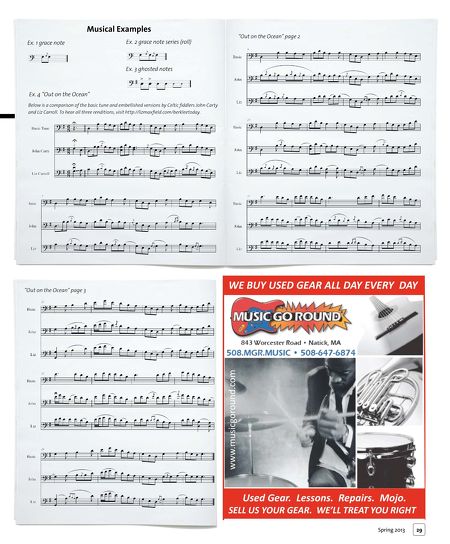

THEWOODSHED Micro-Improvisation in Traditional Irish Music By Liz Davis Maxfield '09 Classical musicians interpret the notes on the page very literally and limit improvisation to an occasional cadenza. Conversely, jazz musicians get their kicks from straying from the written page, using the chords as a starting point for macrolevel improvisation. Irish traditional musicians, however, work with micro-improvisation, a subtle brand of embellishment combining nuances of ornamentation, phrasing, variation, and other expression, all of which flow from an individual musician's personal style. Ornamentation "What is ornamentation? It's the coloring of a note, but it's also a very idiosyncratic personal thing. The way you would do a roll and the way I would do a roll would be different, and that's the beauty of this art form of traditional music." —Neil Martin Liz Davis Maxfield is a performing cellist and teacher. After graduating from Berklee she studied Irish traditional music at the University of Limerick in Ireland as a Fulbright scholar. Like most musical genres, Irish music comes with its own vocabulary of ornamentation. These ornaments are rarely notated in tune books, and it is assumed that players will decide when and how to use them within the parameters of the tradition. The most common Irish ornaments involve a grace note (see example 1) or a series of grace notes (called a "roll," example 2) inserted before or in the middle of an emphasized note. These grace notes are executed so quickly and percussively that the specific pitches of the grace notes are not as important as the rhythmic embellishment they produce. Other common ornaments include vibrato (which is not considered necessary to tone quality) and double stops (playing multiple notes at once). Phrasing "Don't think of music as a combination of notes or dots. Think of curves, lines, or shapes of a continuous motion. It's a wave, not a particle!"—Martin Hayes This lesson was excerpted from The Irish Cello Book published by Berklee Press. 28 Berklee today While the specific phrasing of a tune isn't predetermined, players tend to follow bowing or breathing patterns that add variety, bring out nuances in the melody, emphasize specific ornaments, elongate a phrase, and create gentle syncopation. Musicians also shape phrases through improvised dynamics. However, instead of using accents to emphasize important notes, Irish musicians often use ghosted notes (inverted accents or whispered notes) to deemphasize the unimportant notes. Example 3 compares accented notes, normal notes, and ghosted notes, using note head size to illustrate their relative dynamics. These subtle phrasing techniques account for some of the tradition's unique lilt and timbre. Variation "The more variation the better, so long as it has its roots in the tradition, and serves to extend that tradition rather than destroy it by running counter to it."—Seán Ó Riada Variation in Irish music refers to minor changes to the melody that make the tune more complex and interesting when repeated over and over again in a session or concert. These variations can be composed in advance or improvised on the spot. Because Irish music is driven by melodies rather than chord structures, its melodic variations are more constrained than those in jazz or bluegrass. Rather, the Irish musician walks the line between keeping the melody intact and surprising the listener. Expression "If you constantly keep your mind alert, it can be difficult to fully relax and commune with your instrument on an emotional level. I find that when musicians get to a certain point of relaxation, the interaction between them and their instruments becomes complete."—Siobhan Peoples The expression and emotion that drives Irish traditional music is much more important than virtuosity. The goal isn't to show how fast or high you can play, or how well you can improvise. The goal is to connect with the music, enjoy it, and engage with the listener and other musicians. Depending on the context and motivation of the musician, expression can be used internally (as a means for the musician to connect with the music and the tradition) or externally (as a means for the musician to connect with other people). Expression is impossible to notate, and difficult to teach. But it is one of the most important tools of micro-improvisation in Irish traditional music, as it motivates emotional connection between the music, the musician, and the listener. Style "Musicians who come from the genre of traditional music need to be very careful that they encourage young people to play, giving them the freedom to be who they want to be [musically]. But the young musicians, in having that freedom, need to have respect for the genre, for where [it came] from, and the people who kept it alive when it was difficult to keep it alive."—Seamus Connolly If ornamentation, bowing, variation, and expression are the tools musicians use to color Irish tunes, then style is what guides their use of these tools. Personal style is a multifaceted concept that takes into account history, experience, and taste. The phenomenon of regional fiddle styles has been a matter of discussion since it was first brought to public attention by Seán Ó Riada in 1963 with his radio broadcast Our Musical Heritage. Ó Riada suggested that Irish musical styles, like dialects in language, are specific to local communities. Over time, this idea became so embedded in the discussion and identity of traditional Irish music, that today virtually all Irish musicians claim a regional style as their musical heritage. But these physical boundaries have become decreasingly definable as modern musicians travel, tour, immigrate, and record. Now that Irish music is such a global genre, it's up to the individual to decide which style or styles to imitate and, in essence, which region to call home. Once a musician is comfortable enough with Irish music to try micro-improvisation, the most important nuance is the "voice" of the individual. The Irish musicians who are most notable are usually the ones who are steeped in the tradition enough to be credible, but innovative enough to stand apart. John Carty and Liz Carroll, who are two great fiddlers, exhibit idiosyncratic personal styles that are informed by all of the aforementioned tools and characteristics. They sound simultaneously traditional and innovative. In comparing their versions of "Out on the Ocean," a popular Irish tune, we see their distinctive ornamentation, phrasing, variation, and expression (see example 4). To hear the corresponding recordings, visit LizDavisMaxfield.com/BerkleeToday. The next time you find yourself listening to Irish musicians "turning tunes," see whether you can spot these elements of micro-improvisation. Regardless of the genre of music that you play, perhaps incorporating these elements into your own melodic playing will open new and inspiring possibilities.